Gershwin-Novrasli "Rhapsody in Blur"

Shahin Novrasli & Helene Mercier Arnault

Bayati

WORLDWIDE RELEASE 23 MARCH ON EIGHT ISLANDS RECORDS/DISK UNION, JAPAN

SHAHIN NOVRASLI TRIO w/NATHAN PECK ON BASS AND ARI HOENIG ON DRUMS.

Single & Movie

Based on events during the 2020 Worldwide lockdown

On September 18th renowned Azeri musician Shahin Novrasli released a stunning but brutal animated ‘Short Movie’ for lockdown inspired single ‘Quarantine’.

A tempestuous fusion of jazz, classical and mugham, a traditional Azeri folk artform passed down

through generations, ‘Quarantine’ is an agitated affair, built upon a staccato bass ostinato and a frantic modal topline that instils an unnerving aura over the listener.

Written and produced by Buta.art founder Nasib Piriyev, animated by Slovenian artist Tomi VGN, the video highlights the transcendent spirit of Shahin’s work.

Shahin’s personal evolution began at the age of three when, encouraged by a rich culture of music in his family, he first started playing piano. It’s been both an academic and spiritual commitment ever since. From playing in symphonic orchestras at the age of 11 to his more recent studies of mugham singing, one of the most complex and challenging artforms in Azeri musical culture, his entire life has been characterised by a devotion that’s so intense you see it running through him as he performs.

Best witnessed live, Shahin is a tightly-coiled spring, poised between stool and Steinway like an arrow in a bow. You’re just as likely to hear him reference Joni Mitchell as you are Bach or Vagif Mustafazadeh in his repertoire. This is why a consistent thirst for fusion has become his jazz-mugham signature.

It’s also why he attracted the attention of the legendary jazz pioneer Ahmad Jamal who describes Shahin as one of the best pianists he’s ever heard. They’ve worked closely since meeting in 2014 with Ahmad producing two of Shahin’s most explorative and experimental albums so far; ‘Emanation’ (winner of UK Vibe Best Jazz Album 2017 award) and ‘From Baku To New York’.

With ‘Quarantine’, Shahin has captured the terrifying essence of a global pandemic and affirmed himself as one of the most creative & reflective pianists working at the moment.

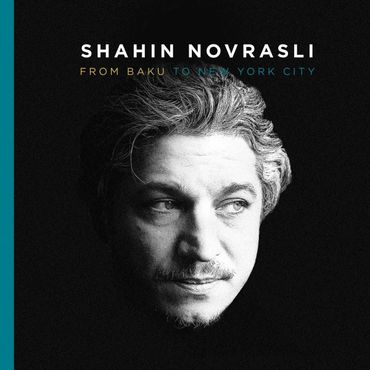

From Baku to New York City

Jazz Weekly

George W.Harris

It’s easy to see why jazz legend Ahmad Jamal endorses as well as produces this album by pianist Shahin Novrasli. As he demonstrates on this trio album with veteran drummer Herlin Riley and bassist James Cammack, Novrasli goes against the prevailing current conventional wisdom and emphasizes space, clarity of style over overwhelming sounds. Obi Wan has taught him well.

He does a deep and dark solo rendition of “Memorize” and a pretty “She’s Out of My Life” as well as some wonderful teamings with Cammack on the restraining “Cry of Gulchura” and suavely grooved “Stella By Starlight.” His left hand shows strong digital muscularity on the clear “Both Sides Now” and he fires away with his six shooter with Riley on “Shahin’s Day” and a race to the finish line on the runaway “Salt Peanuts.” Speed and dynamics are used as a means to an end, not an end in themselves, as Novrasli changes them like mixing brushes for a painting. A real joy!

The Rehearsal Studio

Stephen Smoliar

This past Friday I wrote a “heads-up” article about the latest album from jazz pianist Ahmad Jamal, Ballades, which will be released by Jazz Village this coming Friday. That date will also mark the release of a new album by Jamal’s latest protégé, Azerbaijani pianist Shahin Novrasli. Also released by Jazz Village, the album is entitled From Baku to New York City; and, like Ballades, it is currently available for pre-order through its Amazon.com Web page.

Listening to any album, particularly one of jazz piano, in the context of a Jamal album is a tall order; but it does not take long for the attentive listener to appreciate Jamal’s interest in this young pianist. He shares with his “protector” a clarity of touch in his approach to the keyboard; and, like Jamal, Novrasli is not afraid to explore the potential of high-density embellishing patterns. From a technical point of view, Novrasli brings a prodigious knapsack of skills and thematic tropes to the performance of all of the tracks on his new album; and these are skills that definitely cannot be ignored.

On the other hand, the album gives the impression that Novrasli is “trying on for size” a variety of different approaches to repertoire. There is an unmistakable fire in his take on Thelonious Monk’s “52nd Street Theme,” enough to leave me wondering how he would rethink what the most adventurous pianists were doing in the middle of the last century (Bud Powell coming to mind almost immediately). The other track that bears witness to that time is Dizzy Gillespie’s “Salt Peanuts,” supposedly written in partnership with Kenny Clarke. “Salt Peanuts” is a bebop “encoding” of George Gershwin’s “I Got Rhythm;” but Novrasli keeps the source as meticulously encoded as Gillespie did.

Indeed, he approaches Gillespie’s theme with an extended introduction based on repetitive structures that could easily have been lifted out of one of the piano études composed by Philip Glass (but definitely was not appropriating any sense of Glass). However, once drummer Herlin Riley joins Novrasli, we know for sure that we are not in “Glass territory,” even though the “Salt Peanuts” tune has yet to emerge. (I did not take out a stopwatch while listening to this, but it is the sort of extended introduction to an exposition that can be found in the first symphonies of both Johannes Brahms and Gustav Mahler.)

A similar introduction is encountered on the “Stella by Starlight” track. Once that introduction has run its course, Novrasli seems more inclined to settle into the tune as Victor Young wrote it, rather than reflecting on some of the more memorable latter-day treatments, such as the one that became part of Miles Davis’ book. On the other hand, since I confess to being no great fan of Joni Mitchell, I would have preferred to find “Stella” on the opening track, while “Both Sides Now” (which begins the album and will always be more than a little too syrupy for my tastes) would have been better situated near the end!

Three of the tracks reflect on Novrasli’s roots in Azerbaijan, only one of which is composed by Novrasli himself. These selections are based on both classical and jazz Azerbaijani sources. However, when compared to other classical encounters with such sources that I have previously enjoyed, I cannot say that I was aware of any “cultural roots” behind Novrasli’s interpretations. There are the occasional augmented seconds; but they are a bit like Aristotel!s lone swallow that “does not make a summer.”

Personally, I am more than content to listen to From Baku to New York City as an “emerging talent” recording. I shall probably revisit it from time to time. However, I am more interested in the directions that Novrasli’s “further emergence” will take him.

Album Presentation

CEO & Founder